It is with heavy hearts we announce the passing of Alastair Niven LVO OBE, one of the Prize’s longest-serving Trustees and Advisory Council members. Alastair – who retired from the Board in 2024 left an indelible mark, not just on the Prize but on the literary landscape. With a life dedicated to the arts, he leaves behind a legacy of what it means to be a cultural producer, facilitator and advocate.

Alastair served as Principal of Cumberland Lodge, Windsor, from 2001 to 2013. Prior to that, he was Director of Literature at both the British Council and Arts Council England. His academic career included posts at the Universities of Ghana, Leeds, Stirling, London (SOAS), Aarhus, and Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford.

A distinguished literary scholar, Alastair authored books on D. H. Lawrence, Mulk Raj Anand, Raja Rao, and others, and contributed over a hundred articles and book chapters.

His long-standing association with the Commonwealth began as a Commonwealth Scholar and continued through roles such as Chair of the Commonwealth Writers Prize advisory committee and Editor of The Journal of Commonwealth Literature.

He also served as a Trustee of the Council for Education in the Commonwealth, President of English PEN, and Chairman of the UK Council for International Student Affairs.

Chair of the Board of Trustees, Ellah Wakatama OBE commented: Alastair was a cherished colleague. He brought wisdom, experience and a true passion for the arts as a constant and hardworking member of the Caine Prize family in various capacities over the years. I will miss his serious approach and affable manner, and his support.

Advisory Council members honour Alastair Niven, reflecting on his role as a colleague, friend, and literary champion.

Zodwa Nyoni: “I'd never met Alastair when he reached out to me to introduce himself and the work of the Caine Prize in 2022. He spoke of how he'd been following my writing career. It was such an unexpected, kind and earnest email. From then on, we spoke of the stories we enjoyed and places we'd travelled. He invited me to join the Advisory Council. I was honoured as I'd too been following the Prize and read the stories. In the short time I knew Alastair and had the opportunity to work alongside him on the Council, I appreciated how welcoming and committed to writers he was; and how passionate he was about the Prize and its growth. He will be dearly missed”

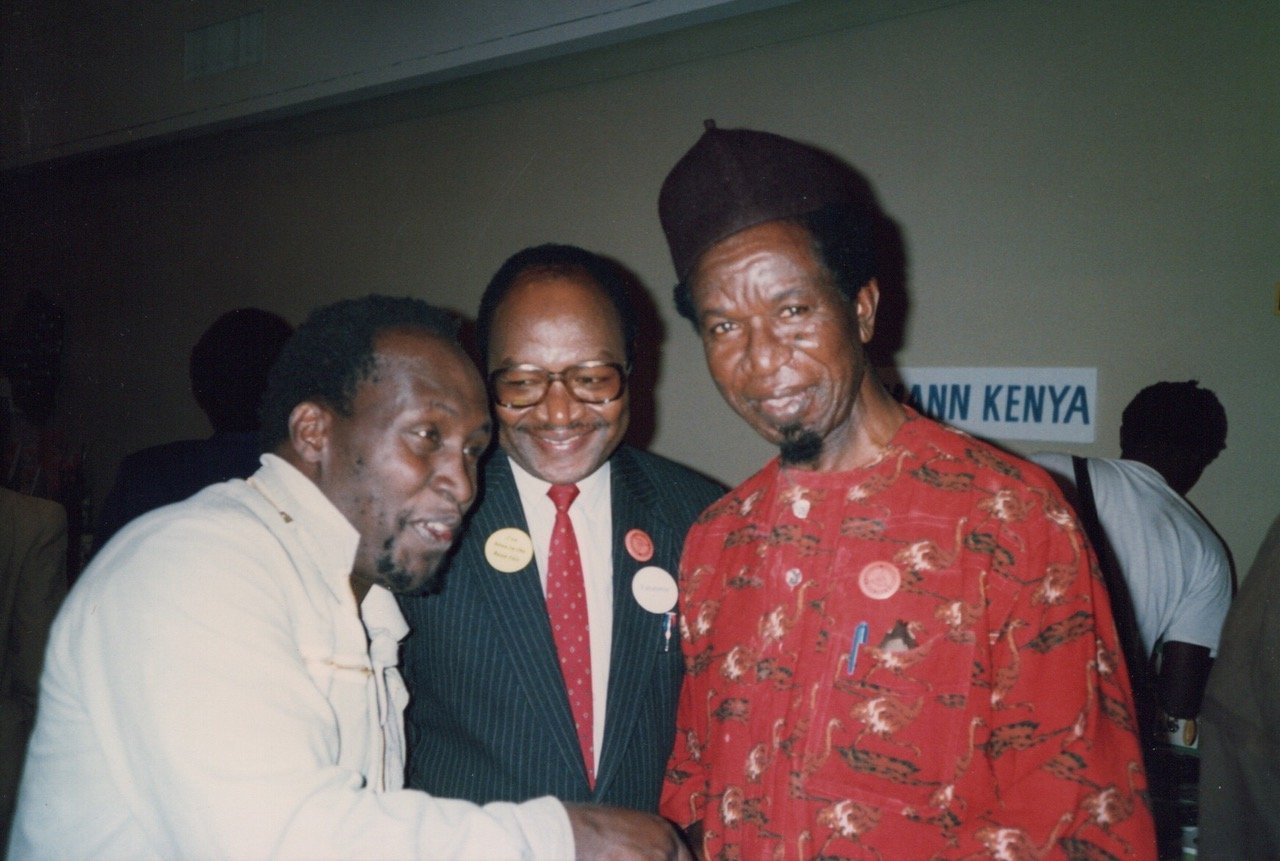

Margaret Busby: “It is difficult to process the sad loss of Alastair Niven, someone who featured in my life for more than half a century. As director of the Africa Centre (1978-84), succeeding founder and inaugural director Margaret Feeny, Alastair oversaw numerous exciting ventures involving literature (the Covent Garden building was always a welcoming venue for book launches), theatre, music and art, that helped consolidate its continuing reputation beyond his tenure and the Centre’s eventual move from central London.

“I saw it as a compliment that Alastair from time to time called on my judgement, whether to be on staff interviewing panels, or other committees. He was astute in the role of Literature Director of the Arts Council, for a decade from 1987 (I gave evidence at his request in one extraordinary case when a writer took legal action on the grounds of being discriminated against as a white applicant for a literature bursary that was specifically for writers of Afro-Caribbean or Asian origin), and we kept connected during his subsequent role as the British Council’s director of literature. I have fond recollections of one particular British Council trip to Paris in 2000 to participate in an Anglo/French seminar, travelling with Alastair on the Eurostar together with a brilliant group of writers, including Caryl Phillips, Andrea Levy, Abdulrazak Gurnah, Denise Narain DeCaires, Zadie Smith, Don Paterson, and of some memorable off-the-record conversations to which Alastair was a witty and entertaining contributor.

“He excelled in every position he held – whether heading up Cumberland Lodge or chairing the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for a couple of decades – and it was a privilege to have professional opportunities to work with him.

“Both having shared time on Caine Prize boards over the years, we had been looking forward to collaborating on a volume of contributions to commemorate the Prize’s unmatched history, and discussing the way forward gave us a delightful reason to meet a couple of times last year, at the Athenaeum as well as at the current Africa Centre (together with Vimbai Shire).

“Advice he gave, drawing on a life of unique personal experience, was ever considered, principled, sound and immensely valuable.

“But beyond all else, Alastair was a friend indeed.”

Vicky Unwin - “I have known Alastair since I was a 21-year-old graduate trainee at Heinemann, and he was the Director of the Africa Centre. This is where we showcased our visiting authors, and we spent many an evening celebrating the best of Africa’s talent. The Africa Centre in those days used to attract eminent leaders and I remember going to a private reception for Jesse Jackson - then a young and emerging politician. These were thrilling times and Alastair was always there - charming, wise, calm and kind. He allowed ATCAL (The Association for Teaching African and Caribbean Literature) and later, Wasafiri, to meet in the bar - once Neil Kinnock dropped in for a drink!

“We remained friends throughout the years, comparing notes on writing memoirs, children, travels, visiting each other’s homes and celebrating milestones. He was always a steadying and calming influence, and this was true of his time as Caine Prize Board member and Chair of the Advisory Council, where he steered us through some rocky times and challenging discussions with grace and equanimity.

“I was so delighted when he invited me to lunch at the Athenaeum at the end of last year - ‘for old times sake’. Always a gentleman, we first had a glass of champagne followed by a delicious lunch, some fine wine (probably a bit too much) but, best of all, we had a good old chinwag, reminiscing about our last forty-plus years' friendship and the literary adventures they encompassed - not least the night he was Chair of the Booker Prize judges and I, heavily pregnant, was representing Chinua who was shortlisted for Anthills of the Savannah…and Penelope Lively won, much to our disappointment.

“That old cliche ‘he will be much missed’ really applies here, but I feel fortunate to have counted him as a good friend. My heart goes out to Helen and Isabella and Alexander.”

Wangui wa Goro: “Alastair’s passing away is a great loss to the literary world and his numerous friends, colleagues, and collaborators. I found Alastair to be a wise, gentle and kind human being. He was a person of conviction, influence and great wisdom. He had deep knowledge, awareness, insight and sensitivity, and focused on what needed to be done, and done properly. I witnessed him navigate difficult moments with great tact on several occasions. I had heard of Alastair before we met in 1984, and later through our mutual dear friend, now departed, the translator and critic, Ranjana Ash who invited us both to lunch.

“We have since had many wonderful collaborations stretching over forty years, ranging from Commonwealth matters to the Arts Council of England and the British Council where he served. Alastair was a stalwart and tireless champion for literature in general, and literary translation in particular, such as through the British Centre for Literary Translation (BCLT) on whose advisory body both Ranjana and I sat, and English PEN. The icing on the cake was our SIDENSI collaboration in the Lost and Found in Translation and Traducture Conference at Cumberland Lodge in 2011 when Alastair was Principal. We were accommodated with great warmth by Alastair, Helen and the staff for a most memorable experience for all of us.

“There are many highlights to our friendship, such as a memorable trip to the Zimbabwe International Book Fair as judges of the 100 African Books of the Twentieth Century where we rode to Marondera and back to Harare with a Kenyan friend. Another was the award ceremony in Cape Town celebrating these 100 best books in the presence of President Mandela.

“We enjoyed precious moments of exchange in private, and I will always cherish these.

“Much more will be heard of Alastair who will be greatly missed. My heartfelt condolences and gratitude to Helen, Isabella and Alexander.”

Dotti Irving: “I’m deeply saddened to hear that Alastair has died. I got to know him primarily through the Booker Prize. My company, Colman Getty, handled PR and event management for the prize and Alastair and his wife Helen were regular guests at the annual awards dinner.

“Alastair had the rare distinction of being invited to be a Booker judge twice. The first was in 1994 when James Kelman was the controversial winner with How Late It Was, How Late and then again in 2014, when Richard Flanagan won with The Narrow Road to the Deep North. I got to know him well in both of those years.

“Alastair and I shared another bond in that we were both Scottish. Many years ago, I took part in a panel discussion about the Booker with Alastair, Penelope Lively and Neel Mukherjee. When we were asked by the sound technician to describe what we had had for breakfast – a standard recording procedure to establish satisfactory sound levels – Alastair explained very earnestly that he had porridge every day from the first of October to the 31st of March and then on the first of April he switched to muesli for the following six months. That was so Scottish of him! I teased him about it every time I saw him, and the first of April and the first of October never come round without my thinking of him.

“Alastair was a good man and he will be much missed. I send my sincere condolences to Helen and his family in their loss.”

Nana Wilson-Tagoe: “I am only now realizing I have known Alastair personally and professionally for over 40 years! We met through our mutual friend, Kofi Agovi, a good friend of Alastair and Helen when they were both single and teaching in Ghana. Kofi shared a personal bond with Alastair and Helen because of what he often called his personal ‘magical’ manoeuvring in their meeting and eventual marriage. I was drawn into their bond, and I too claimed Alastair as a fellow Ghanaian.

“The connection paid off handsomely in 1985 when as a newly arrived Chapman Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, I struggled to set up a seminar series on Commonwealth Literature. I quickly sought Alastair’s help, and he graciously came to my aid, introducing me to his contacts and participating in most of the seminars.

“I worked with Alastair and others on various other literary projects – BBC panel discussions, the Commonwealth and Caine Prize, the 100 Best Books in Africa project, the Zimbabwe Book Fair- and at all these collaborative events, Alastair was a clear-thinking, incisive, witty and kind presence. He gave so much of his time and talent to the exploration, dissemination and promotion of literature, and his indelible footprints are everywhere in Commonwealth, African and International literatures. I mourn Alastair as a friend, a fellow Ghanaian and a literary brother and I extend my deepest condolences to Helen, Alexander, Isabel and their families.”

--- Additional Comments and Tributes to note ---

Further tributes to Alastair Niven have been posted online by numerous friends and admirers:

Read the tribute in the Guardian which includes comments from Ben Okri and Bernadine Evaristo here.

Read the tribute by the Africa Centre, UK written by Olu Alake here.

Read the tribute by Stephen Spender Trust written by Jonathan Heawood here.

Read the tribute by English PEN here.

Read the tribute by Cumberland Lodge here.

--- End ---