Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o was my passport into publishing. Aged 21 and leaving university, I saw an advertisement for a Graduate Trainee at Heinemann Educational Books. I stated that the reason I was applying was because I had read A Grain Of Wheat and, having been born and brought up in East Africa, felt a great affinity for African writers such as James Ngũgĩ, as he was then known.

I arrived at Heinemann in 1979, in good time to see the publication of Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary in 1981, which was written on government lavatory paper. In the run-up to its publication, he was a frequent visitor to our offices in Bedford Square and it was thrilling to meet him there, go to lunch, to The Africa Centre or even the pub with him. Despite being superficially quiet and softly spoken, he had a great sense of humour and was good company. In those early days of his exile he was pretty hard up, and Heinemann, under James Currey’s benign leadership, became a second home and benefactor to him, as it was to many other writers such as Dambudzo Marechera.

We saw a lot of each other over the years before he went to the US. On one occasion, Alan Hill, Heinemann’s founder, James Currey (AWS publisher) and I, were taking Chinua and Ngũgĩ to lunch; Alan had chosen the Institute of Directors and, despite both our esteemed authors wearing formal African shirts, they were not allowed in without a tie. Alan and James were both mortified, and our writers quite rightly refused to wear the ties proffered by the maître d’ to slip over their fancy shirts.

Ngũgĩ was central to the re-launching of the African Writers Series in 1986. The price of oil and the international financial crisis meant that African countries were no longer able to import books; for the AWS to continue to publish new writers, we had to find new markets, so we turned our attention to US universities and their African literature courses, and the UK trade market. In order to get shelf space in bookshops, we decided to upgrade to B format/trade paperback and commission colourful covers.

Here you see me presenting one such piece of original artwork to Ngũgĩ at the launch. There was a bit of outrage over the loss of the orange and black, but it was a small price to pay to continue to publish. Ngũgĩ was a staunch supporter during this frenetic and difficult period, as was Achebe: they both put the survival of the series above anything else. In Ngugi’s case it was more nuanced as he had already begun to publish in Gikuyu and allowed the AWS to publish the English translations as Devil on the Cross (1980), I Will Marry When I Want (1982) and Matigari (1989).

In this photo are Alan Hill, Ngũgĩ, Ali Mazrui, me with a scary hairstyle, and Chinua Achebe, who were amongst the many writers present.

In another photo we see a much more relaxed Ngũgĩ chatting to the poet Grace Nichols.

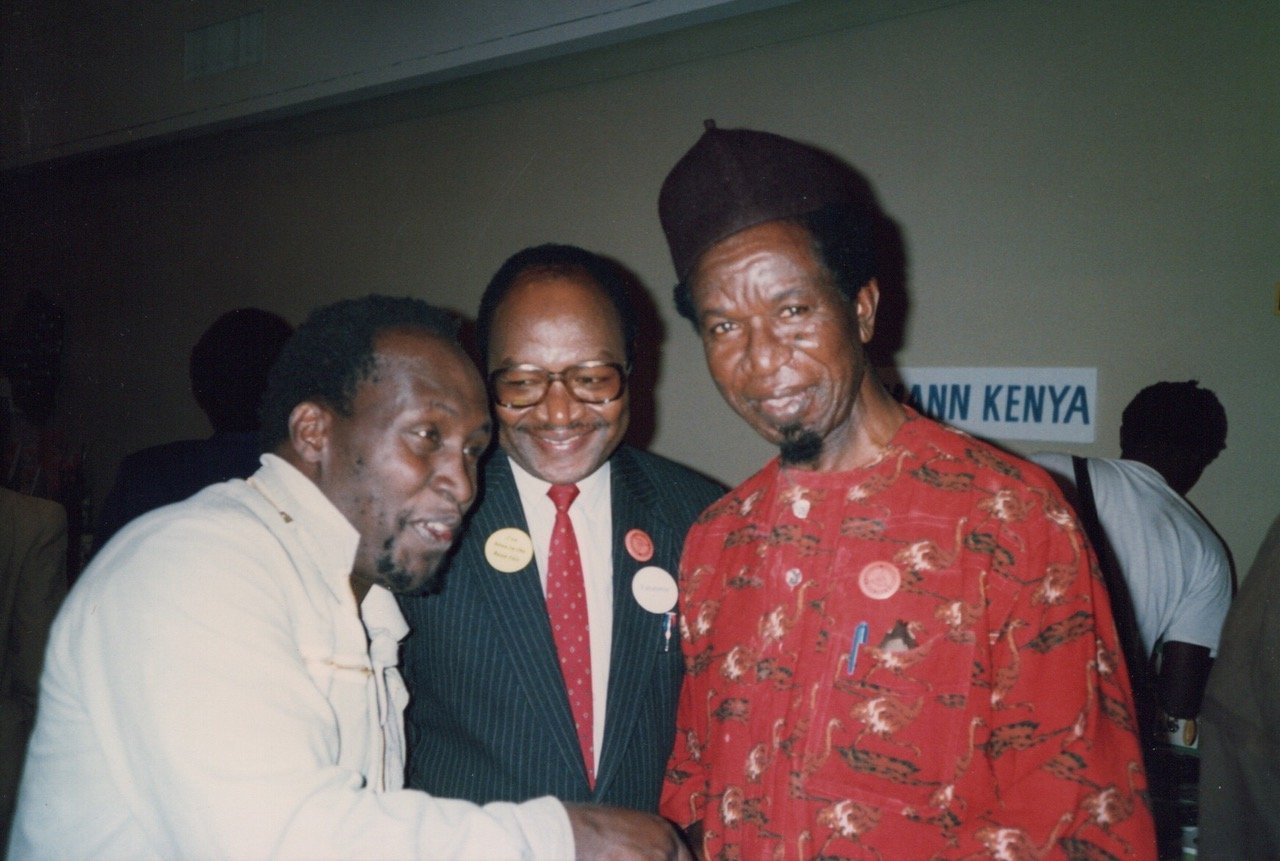

Ngũgĩ was always in demand on the conference circuit, and he came with us to the Zimbabwe Bookfair on at least one occasion. Here he is enjoying a joke with AWS author Cyprian Ekwensi, and Henry Chakava, Managing Director of Heinemann Kenya and one of his greatest friends and champions, supporting him through many arrests and other political confrontations with the authorities. Henry died in 2024.

It is extraordinary to think that I knew Ngũgĩ all my working life; his intellect and beliefs changed the course of African literature during his lifetime and he really deserved the elusive Noble Prize in recognition of his contribution to the genre, and indeed to literature as a whole.

Vicky Unwin, London, June 2025